Queen of the plains: Charlotte Plains Station, Qld

With headwaters in the Carnarvon Range near Tambo, the Warrego River flows generally south through the middle of the region for 1380km before petering out in swamps near Louth (NSW). The river is joined by 37 tributaries, and has several outflowing creeks and anabranches, including Widgeegoara Creek through Charlotte Plains.

Annual rainfall in the river’s catchment is low and very erratic, as little as 250mm on the southern plains, and evaporation is high. Consequently, the Warrego and its distributaries flow intermittently, according to the season and regional rainfall. Some years pass without any flow, and the river is reduced to a chain of permanent waterholes. But in very wet seasons typically associated with La Niña events, the river may reach the Darling.

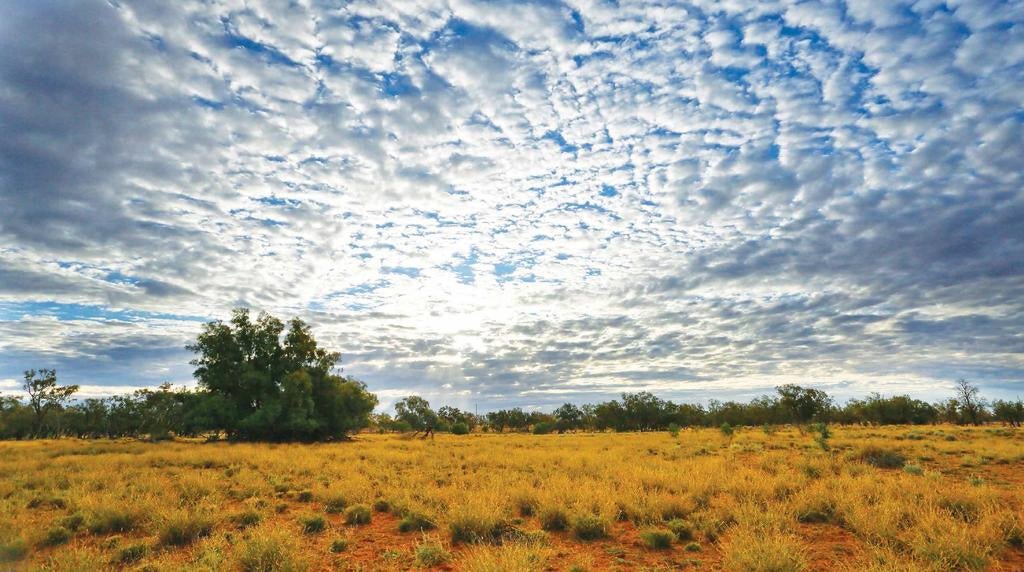

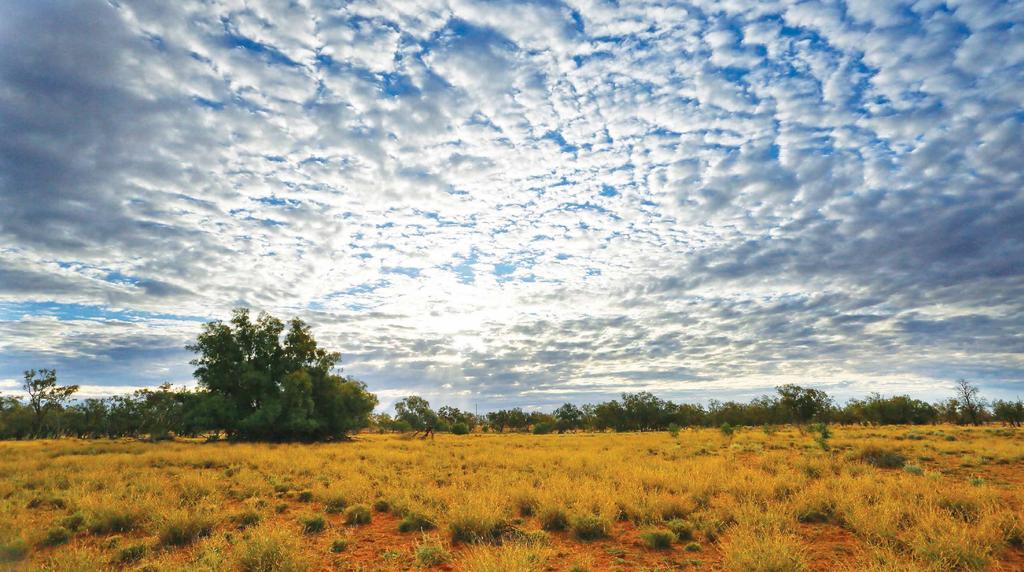

The plains are covered with native grasses on rich clay soils and saltbush shrubland on less fertile red earths.

Drought-tolerant mulga (Acacia aneura) grows in dense woodlands on sandy soils, but on the stony ridges it is stunted and sparse. Alluvial floodplains support a variety of eucalyptuses including red bloodwood, poplar box, coolabah and silver-leaved ironbark, interspersed with white cypress pine, beefwood and woody shrubs. At least 747 native plants have been recorded in the region, together with wildlife species including 256 birds, 56 mammals, 94 reptiles and 23 amphibians.

The Great Artesian Basin

Charlotte Plains — and indeed one-fifth of the Australian continent — lies atop the Great Artesian Basin. Storing an estimated 64,900 cubic kilometres of groundwater, the Basin is the largest underground freshwater resource in the world. The water is held in a porous sandstone layer (aquifer) compressed between strata of impermeable rock deposited alternately between 60 and 240 million years ago. Trapped within the aquifer, the water is pressurised and heats to between 30-100 degrees. It may force its way to the surface through weak points in the substrate to form ‘mound springs,’ or it may be tapped by drilling a bore into the aquifer. Today there are some 50,000 bores across the Basin, sustaining more than 120 towns and hundreds of properties and enabling the development of pastoral, agricultural and extractive industries worth an estimated $13 billion annually.

The human landscape

Indigenous people of many nations lived in the Mulga lands for more than 25,000 years before the arrival of Europeans. The Kunja people are the Traditional Owners of the area around Cunnamulla. The Warrego was an integral part of their daily lives and still has great cultural and spiritual significance for their present-day descendants.

In 1846, Thomas Mitchell was the first European to pass through the region while searching for a route to the Gulf of Carpentaria. He was followed a year later by Edmund Kennedy, who explored the Warrego River plain and reported favourably on the pastoral potential of the area’s abundant Mitchell grass. A further report by William Landsborough after his 1862 expedition triggered an influx of settlers who found the open plains ideal for grazing sheep. Initially, settlement was restricted to the river corridor, but the opening of artesian bores enabled graziers to move far out onto the plains.

In the mid-1860s, Samuel and Thomas Smith took up a pastoral run where two major stock routes intersected at a large waterhole on the river. Cobb & Co established a coach depot at the junction, which became the focus of the Cunnamulla settlement, with transport links throughout southwest Queensland and to the Darling River at Bourke.

A dappled sky over the plains of Warrego

Present-day Cunnamulla stands on the east bank of the Warrego River, near the junction of the Mitchell and Balonne Highways, 750km west of Brisbane. With a population of around 1140, the town is the administrative seat and service centre for the Paroo Shire, which covers an area of more than 47,600 square kilometres. The shire’s major industries are grazing of beef cattle and sheep for wool production, with goats developing as another livestock resource. Charlotte Plains is a prominent part of the local tourism industry which is also making a significant contribution to the regional economy. In 2021, the station was the national winner of the Grey Nomads Award for Tourism.

Station history

When the station’s pastoral lease was first taken up in the 1860s, it was called ‘Turnworth’ and covered almost 156,000 hectares. Around 1874, it was purchased by Scottish brothers Archibald and Peter McDonald, who renamed the property ‘Charlotte Plains,’ reputedly in honour of their mother.

Like many stations on the Warrego Plains, the property was devoted to grazing sheep for wool, with flock numbers fluctuating in step with the seasons. A 22-stand shearing shed was constructed on the property in about 1887, and between 56,000 and 67,000 sheep were shorn each year, with the highest number recorded at 104,000. The station regularly produced as many as 95 bales of wool in a season, peaking at 1484 bales in 1914. Bullock teams hauled the bales to the railhead at Cunnamulla for markets on the coast via Charleville and Roma.

In 1923, Charlotte Plains was purchased by A.B. (Bunny) Nagel. Bunny earned his nickname for erecting a netting fence around the station perimeter — at a huge expense — to protect the pastures from depredation by rabbits. Bunny’s son Gordon inherited the property and managed it with his wife Lorraine until his death in 1974. Lorraine came from a pioneering family in North Queensland, was educated in Sydney, and became something of a local legend during her 56 years on the property. In 2002, the station passed to their daughter, Robyn Russell (née Nagel), who continues the family’s pastoral traditions.

Charlotte Plains today

Charlotte Plains is somewhat smaller now, though still a sizeable 27,000ha, and the woolshed only operates four stands. While sheep remain the focus of operations, some changes have been made to the composition of the flock and stock rates in response to persistent drought. Sheep numbers have been reduced to around 1500, of which about two-thirds are Merinos that yield fine grade fleeces of an average 19-20 microns. The rest of the sheep stock includes South African Dohne-Merino for wool and meat and ‘Aussie Whites’ for meat only. A herd of 120 Hereford-Angus-cross cattle and Droughtmasters has been introduced for diversification.

Artesian water on Charlotte Plains

The first successful artesian bore in Queensland was sunk near Cunnamulla in 1887. Five years later, a bore was drilled on Charlotte Plains to a depth of 561 metres and a cost of nearly £2000. Crystal clear artesian water flows continuously under natural pressure at a steady rate of 2.3 million litres per day and comes out of the bore head at about 42 degrees. It feeds into a 145km network of bore drains across the property to supply the stock and, since 2013, to fill tanks at the homestead and shearers quarters for domestic use.

The open bore drains also serve an important environmental function. Several outlets at the bore-head feed large pools and channels surrounded by aquatic vegetation that provides a wetland habitat for many kinds of birds — egrets, herons, spoonbills, pelicans, dotterels and plovers to name a few. Further afield, the drains sustain huge flocks of cockatiels, corellas and galahs, while finches populate the native grasses, and clusters of cypress pine and coolabah are home to gaudy ringnecks. All rely on this life-sustaining water in the semi-arid country.

A prime attraction of the station are baths established at the bore-head for visitors who wish to take advantage of the artesian water’s therapeutic benefits. The water is saturated with naturally occurring minerals such as magnesium, calcium, potassium, iron, sulphates and bicarbonates. By immersion in the hot baths, the trace elements rejuvenate and hydrate the skin and are absorbed into the body to relax muscles, ease tired joints and relieve stress. The baths are sited on elevated platforms overlooking the surrounding wetlands and the heated water makes bathing under the stars at night a really unique outback experience.

The Queensland government’s Water Plan (Great Artesian Basin and Other Regional Aquifers) 2017 provides a new framework for the management of the state’s Basin groundwater, and mandates that all uncontrolled bore and drains be made watertight by 2027. This process has already begun on Charlotte Plains with piping and troughs installed to half the property. One day, all the bore-drains will be replaced, but Robyn and her two sons hope to retain the bore head structure for posterity, to maintain some environmental flow for the wildlife, and for the therapeutic baths.

Ecotourism

The artesian baths are just one of many activities on offer at Charlotte Plains. The artesian wetlands can be explored by canoe or enjoyed by swimming. Station tracks make bushwalking easy in the surrounding forests, there are excellent opportunities for birdwatching and photography, and the clear, clean country air is perfect for stargazing at night, unspoilt by city lights.

Many station tracks are open to guests for self-guided fourwheel driving, although they may be restricted during wet conditions. Also, depending on the time of year, it’s possible to experience station activities firsthand, such as animal feeding, shearing and ‘delving’ for yabbies.

This dray is a relic of the station’s bygone pastoral era

One of the most popular activities is a station tour guided by Robyn, whose wry commentary is informed by her family’s association with this property for almost 100 years. Travelling in the air-conditioned comfort of the station bus, the tour takes you on a fascinating journey through the station’s history, with highlights that include the artesian bore; Jack’s Hut, initially occupied and named after Jack Emblem, a drover and bullocky who worked for the Nagels for 50 years, and later the sometime-home of ‘Willie,’ a charismatic cameleer who provided wagon rides to visitors; the 130-year-old woolshed brought to life by Robyn’s yarns about sheep, wool and shearing; the station cemetery with its mute tributes to the station’s pioneers and their triumphs and tragedies on the red sand plains; and the station’s museum housing memorabilia from bygone days.

Campign and accommodation

The station offers several options for camping and accommodation. If you’re bringing your own van, camper trailer or tent, you can park them at two locations. The Shearer’s Camp is a short distance from the homestead and has both powered and unpowered sites with facilities that include hot showers, flush toilets, a laundry and a communal fireplace. At the artesian bore, an open campground has almost unlimited space for unpowered camping in rigs of all sizes, with toilets, showers, fireplaces (wood available) and a camp kitchen, not to mention the use of spa baths nearby. Generators are permitted between 7am and 10pm.

For those who are free-wheeling and travelling light, the shearers quarters comprises 8 rooms configured as double or twin share (linen provided and air conditioning available in some), with a camp kitchen, bathroom facilities and shared laundry. Special packages are available to small groups (up to 16) who wish to book the entirety of the quarters.