Adventurous travels tracing Paroo River

Rated “main unsealed” on most maps, this 425km route is a good dry weather track, generally wide and well-maintained, with the occasional cow or kangaroo the only hazards. Along it, travellers will encounter artesian mud springs, Ramsar wetlands, secluded riverside camps, historic pubs, Henry Lawson and precious opals.

Paroo Country

Embracing a catchment of 76,000sq.km, Paroo Country is a mosaic of flat sandplains, undulating dunefields and ranges of long, low hills. Much of this semi-arid landscape receives less than 300mm of rain each year, barely enough to maintain a flow in the river. From its source in the Warrego Range, west of Charleville, the Paroo meanders generally south for 1,210km in a series of semi-permanent waterholes, lakes and wetlands that connect as a running stream after plentiful rains. Though considered a tributary of the Darling, the Paroo usually ends on a floodplain (the Paroo Overflow) east of White Cliffs, about 270km south of the Queensland border. Rarely, and only during major floods, does the river join the Darling just upstream of Wilcannia.

Indigenous Culture

Paroo Country straddles the traditional lands of many Aboriginal nations, who lived here for more than 25,000 years before the arrival of Europeans. (‘Paroo’ is a variation on Paruntyi, a clan of the Paakantji people.) The river, lakes and floodplains were crucial to their survival, providing water, food and other material resources, as well as having ceremonial and spiritual values. Evidence of their occupation occurs at many sites across the region in the form of stone arrangements, native wells, scarred trees, artefact scatters, quarries, hearths, middens and burial grounds. Their modern descendants maintain a deep spiritual connection with the river, and some of its associated wetlands have particular significance as story places and sites for cultural activities.

European History

Several European explorers passed through the region in the 1840s but it was not until the 1860s that pastoralists took up land for grazing sheep. In the early years, settlement and grazing was confined to the river corridor but expanded further afield as artesian bores created reliable sources of water for stock and people. As the pastoral industry boomed, coaches, railways and river boats connected far-flung stations to markets, and towns grew up at transport hubs to service the burgeoning enterprises. Today, the region is sparsely-populated and the only settlements along the Paroo are Eulo, Hungerford, Wanaaring and White Cliffs.

Eulo

The small town of Eulo sits on the Bulloo Developmental Road (aka the Adventure Way) 66km west of Cunnamulla. The site was chosen for settlement in the late 1860s because of its proximity to a semi-permanent waterhole on the Paroo River. When opal mining was at its peak in nearby Yowah, in the 1880s, Eulo was a bustling regional service town with three hotels and a gathering place for thirsty miners. Today, with less than 100 residents, the town consists of little more than a single hotel (the ‘Eulo Queen’), a general store (with fuel) and a few houses. The hotel has a small facility at the rear to accommodate caravan travellers. Alternatively, free camping (with no facilities) is available on the banks of the river near the bridge to the west of town.

Eulo is renowned for a cluster of artesian mud springs (the ‘Eulo Springs Supergroup’), comprising about 40 vents from which milky-grey mud bubbles to the surface from deep underground. Estimated to be 20,000 years old, the mud is rich in minerals which give it a slick, silky feel. The therapeutic benefits of this ancient slurry can be enjoyed at the Artesian Mud Baths on the outskirts of town, where patrons can recline in large bath tubs of it in a rustic, open-air bathhouse, with light refreshments.

Currawinya National Park

Five kilometres west of Eulo, a wide gravel road heads south towards the village of Hungerford on the border. After 65km, it enters the Currawinya NP, one of Queensland’s largest and most important conservation reserves, straddling the Paroo River. Nearly half of the park’s 344,000ha area consists of the Currawinya Lakes Ramsar wetlands, a complex of lakes, riverine waterholes and artesian springs, which support a rich diversity of wildlife, including huge aggregations of waterbirds in numbers rarely seen outside Kakadu or Lake Eyre.

The Park was formed by the acquisition of five former pastoral properties - Currawinya, Caiwarro, Boorara, Werewilka and Bingara - that were established in the mid-1860s for grazing sheep and cattle. Tangible reminders of this pastoral heritage exist today at the Currawinya homestead complex and shearing shed, the ruins of old Caiwarro Homestead, and other artefacts scattered throughout the Park. The best time to visit is between May and October, when the Park offers excellent opportunities for no-frills bush camping, bird watching and fourwheel driving, as well as swimming, canoeing and fishing in the river and Lake Numalla. Camping permits are required and fees apply.

Hungerford

Twenty kilometres south of the Currawinya ranger station, the road arrives at the tiny village of Hungerford on the border, 214km northwest of Bourke. The settlement began as a drovers’ camp on the river during the 1860s, and was later expanded to include a police barracks and border customs post to collect duty on goods such as wool, and to prevent the smuggling of contraband, especially alcohol.

Hungerford has been a police outpost since the 1860s

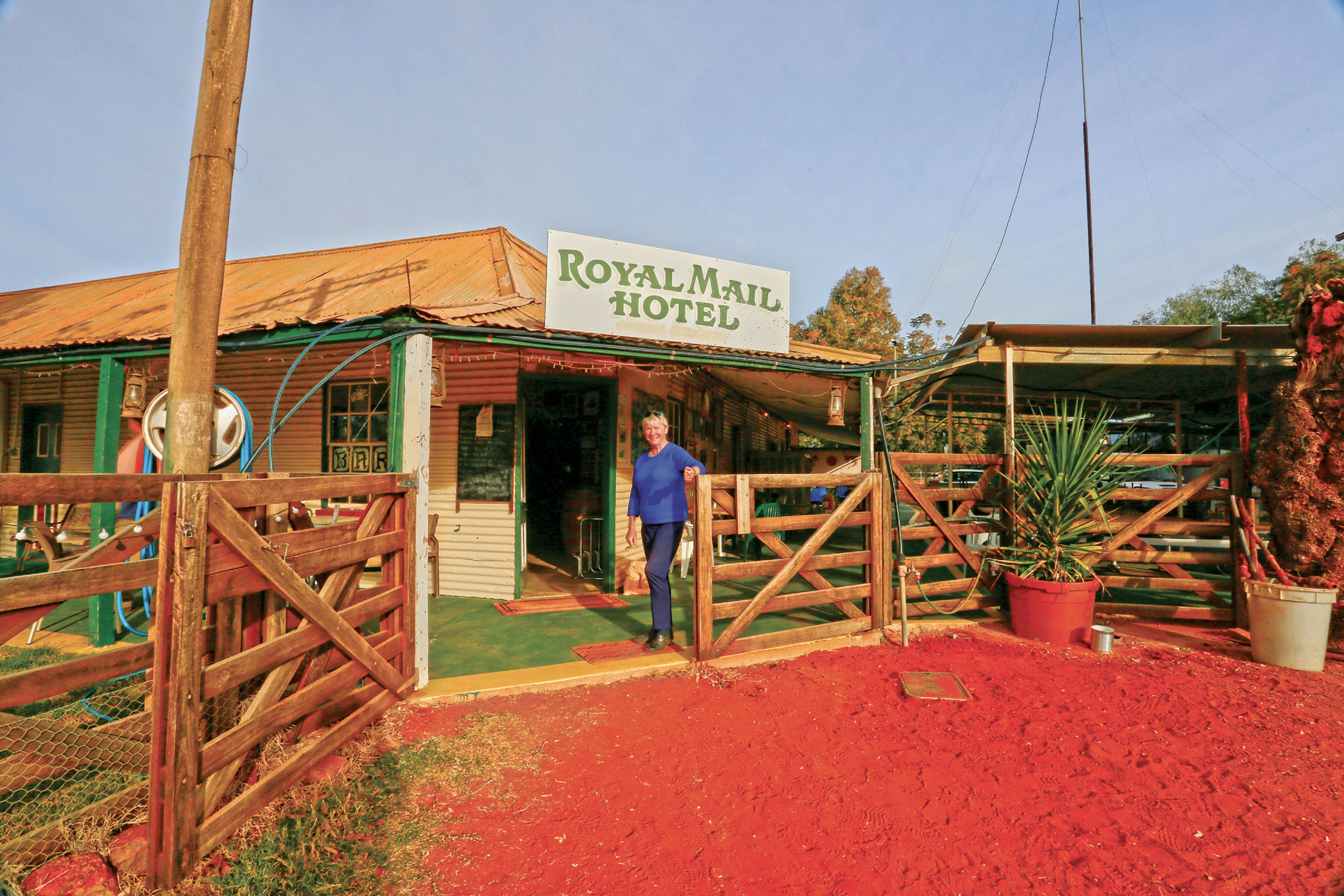

In 1874, the Royal Mail Hotel was built to cater for passing stockmen, bullock drivers and itinerant pastoral workers. A year later Cobb & Co established a depot from which it began running weekly services to Eulo and Thargomindah transporting mail, goods and passengers. In the 1880s, large numbers of rabbits began to invade Queensland from the south, prompting the construction of a barrier fence along the border. Unfortunately, the fence was not completed through Hungerford until 1891, by which time the rabbit migration had advanced well north of the town.

In what has been described as “the most important trek in Australian literary history”, Henry Lawson took three weeks to walk from Bourke to Hungerford during the summer of 1892-3. His aim was to gain first-hand experience of the Australian Bush. He found the country harsh, describing the Paroo as “some old bridle-track”, and didn’t much like the beer (“sour yeast”) they served at the Royal Mail.

Today, the Paroo still flows (when it flows) just north of the town and the rabbit fence still divides the two states, with a large gate for access by travellers. The heritage-listed Royal Mail still stands on the main street near the gate and continues to dispense hospitality (including accommodation and fuel) to locals (less than 30 at last count) and passing tourists. For travellers who choose to stay a while, the Bulloo Shire Council maintains the Southern Cross Caravan Park, with powered and unpowered sites, ablution and laundry facilities.

Wanaaring

Once through the Hungerford border gate, the unsealed road unfurls in a broad ochre ribbon towards Wanaaring through a landscape occupied by unfenced livestock properties. In dry conditions this red clay track is generally smooth and hazard-free (except for stray cattle) but in the wet it would be boggy, if not impassable.

Situated on the Paroo River about 110km south of Hungerford, Wanaaring provides basic services to 140 residents in the form of a public school, post office, police station, hotel, general store and an all-weather airstrip. Long distance travellers will find meals and fuel here, with overnight accommodation at a caravan park or free bush camping by the river. The town hosts an annual gymkhana and rodeo as a fundraiser for the Royal Flying Doctor Service, on which the area’s people depend for emergency medical assistance.

The Paroo-Darling National Park

One hundred and sixty kilometres south of Wanaaring, travellers arrive at the northern section of the Paroo-Darling NP, created in 2003 by the acquisition of the Peery, Mandalay and Arrowbar pastoral properties. It spans 96,000ha embracing the rugged gorges and low escarpments of the Peery Hills, sand plains and dune fields that collectively form a catchment known as the Paroo Overflow. It is here that the Paroo River usually ends its journey from Queensland, petering out in a Ramsar wetland of swamps, channels and ephemeral lakes (Peery and Poloko) that are critical to the survival of diverse plants and animals in an otherwise arid environment. The best time to visit is in the spring after winter rains have replenished the wetlands, which abound with flocks of waterbirds and migratory shorebirds. A formal picnic area provides toilets, barbecues and sheltered tables within a short walk from Peery Lake, in which canoeing and fishing (with a licence) is permitted.

The bridge over the Paroo River north of Wanaaring

White Cliffs

After the Lake Peery picnic area, the road to Wilcannia continues for some kilometres before reaching a turn-off at Mandalay Road. This grey gravel track heads roughly west for 34km to White Cliffs across an arid, featureless plain carved by several dry watercourses. The town first reveals itself to travellers from the east by an elongated mesa fringed with a variety of structures at the edge of a greyish-pink escarpment - a hint at the origin of the town’s name.

White Cliffs’ raison d’etre is opal. It was discovered in the area by a party of kangaroo hunters in 1889 and intensive mining over ensuing decades established the town as the first commercial opal field in Australia and the largest producer of this precious stone in the world. The local gem is found predominantly in seams through 100 million year old claystone, a conglomerate of marine origin that also contains opalised shells and fossils of prehistoric fish and reptiles. The field is unique for the occurrence of extremely rare and valuable ‘pineapples’, clusters of mineral crystals that have been transformed into pure opal.

White Cliffs has a desert climate, with mild winters and extremely hot summers in which temperatures typically exceed 40 degrees. Pioneering miners were able to endure this unbearable heat in their underground diggings and got the idea to convert their old shafts into homes. Soon, the rest of the town’s residents began to follow suit, burrowing into the hills to escape the scorching summer heat. Some of these early dugouts may be seen in the walls of the hill near the Red Earth Opal Café, in an area known as ‘The Blocks’.

Caravan park at White Cliffs

Today, there are around 140 subterranean homes and two underground motels, one of which boasts a café, shop and artwork gallery. Above-ground accommodation can be found at the local hotel and the White Cliffs Opal Pioneer Reserve Tourist Park.

Local Contacts:

Cunnamulla Visitor Centre (Website)

Queensland Parks Booking (Website)

Wanaaring Store & Caravan Park (Website)

White Cliffs Outback Store & Tourist information (Website)