Bungle Bungle Offroad Rumble

Mum was a human measurement of sketchy dirt roads when I was a kid. The tougher the terrain, the tighter Mum’s fist would grip around her seatbelt. If she had her eyes shut and two hands clenching the belt — oar-in-a-sinking-canoe-on-the-Daintree style — you knew it was bad.

That is the enduring image I have of the road into the Bungle Bungles, circa 1988, a year after the area was declared a national park. We’d unhitched the family caravan in Kununurra and hit the dirt with a tent, the view through the windscreen of our Ford F100 jolting from a panorama of bulldust to sky with each stomach-lurching dip. Back then, it was unthinkable to drive a caravan into the national park. I remember Dad scoffing at a bloke attempting the track in a low-clearance Subaru, but today, single-axle offroad trailers are permitted.

A WORTHY DETOUR

Purnululu National Park, the Indigenous name by which the Bungles are now known, is a striking UNESCO World Heritage-listed site, located in Western Australia’s East Kimberley. It’s a journey to get here — about 10 hours by road from Broome along the Great Northern Highway, or a 300km drive south from Kununurra. For those tackling the legendary Gibb River Road, the park is a hefty detour, but it’s worth every inch of bitumen and battered gravel.

Purnululu — meaning ‘fretting sands’ in the Indigenous Gija language — is an immense geological wonder, famous for its striped ‘beehive’ domes. Bungle Bungles is thought to be a corruption of ‘Bundle Bundle,’ a local grass. Yet the magnificent sandstone formations occupy less than a quarter of the 240,000ha park. Not to be overshadowed are the equally dramatic gorges, chasms, peaks and valleys, harking back 360 million years.

All this was hidden from the outside world until 1983, when a flyover documentary film crew ‘discovered’ the site, catapulting Purnululu into the global spotlight. In 2003, Purnululu was inscribed on the World Heritage List, UNESCO describing the beehive domes as the most outstanding example of cone karst sandstone in the world: “unrivalled in their scale, extent, grandeur, and diversity.”

THE DRIVE

The national park is accessible via a 53km 4WD track off the Great Northern Highway, 108km north of Halls Creek. There is a free camp near the turnoff where many people opt to leave their vans, but we choose to store our 22ft family caravan at the Bungle Bungle Caravan Park at Mabel Station. It’s 1km off the highway en route to the park, and enables us to set off early after an overnight stay.

We move the caravan into the storage area, lower the tyre pressures on our Ford Ranger to about 30psi, and hit the road. I’m anticipating a journey of corrugated misery, but the road is in remarkably good condition. (Disclaimer: we travelled early in the season. Be mindful that conditions are variable and there are many tales of much rougher rides).

The road carves a sinuous path over red-dust hills speckled with spinifex, through gullies lined with snappy gums and onto an open plateau — the hip bones of the Bungle Bungle Range pushing up the sky in a distant repose. There are about half a dozen water crossings to navigate, but they’re of little concern. The largest barely dampens the bonnet, while another squeezes through a grove of pandanus as pretty as a postcard.

The road twists and bends sharply in places, sometimes resembling a BMX pump track, with its curves, dips, and crests. But there are few corrugations. The main hazards come courtesy of potholes and small boulders, concentrated near the water crossings. It takes an hour and 20 minutes to reach the Visitor Centre, the gateway to Purnululu, and the Ranger has barely broken a sweat.

ECHIDNA CHASM AND MINI PALMS GORGE

The start of the Echidna Chasm walk

The national park is divided into two sections — north and south — connected by a semicircular access road hugging the range’s western flank, with the Visitor Centre in the middle. We turn left to explore the northern reaches first. At the very end of the road is Echidna Chasm. We’ve intentionally arrived just before midday when the sun is directly overhead, and Mother Nature flicks the switch on a dazzling diurnal light show.

The 2km-return Echidna Chasm Walk meanders up a dry, exposed creek bed, and over uneven rocks polished smooth by the belt sander of time. Small diamond-backed insects scurry in the sun, and carpets of red and white-budded wildflowers quiver in the breeze. An oasis of green explodes up ahead as we near a fold in the sandstone rock, slipping between a curtain of Livistona Palms. It’s cool in the shadows. Finches flit and scores of perfectly rounded spiderwebs — shimmering like CDs — cling to the enclosing conglomerate walls, pocked and warted like a witch’s nose.

The chasm narrows and we squeeze through a slit into a large natural amphitheatre. On cue, the sun pierces through, burning a blowtorch through the cleft. The walls — 180m high and carved out of a joint in the sandstone over 20 million years — glow iridescent orange, then red. At the rear of the amphitheatre, a small opening leads deeper into the chasm. We climb over rock slabs, up ladders and through crevices with boulders wedged, Indiana Jones-style, above our heads, until the passageway abruptly ends.

On the way back to the carpark, we detour to Osmand Lookout, catching our breath as the billion-year-old rock formations of the Osmand Range splay to the north. A few kilometres south-west of here is the starting point for the 4.4km-return Mini Palms Gorge walk. The trail begins as a wide path through thin forests of Bloodwood eucalypts, Grevillea, and Acacia before converging with another dry creek bed. Soon we are scrambling over conglomerate boulders, around tree roots, and under fallen logs. The walk ends at a viewing platform looking into the ochre jaws of a chasm abloom with Livistona, small saplings washed flat on the sandy creek bed below.

CAMPING OUT

The sun hangs low in the sky when we pull into our campsite. There are two public campgrounds in the national park — Walardi in the south, and the larger Kurrajong in the north. We’ve chosen the latter as the base for our two-night stay. There are 106 unallocated sites across four loop roads, with designated areas for trailers. We find a grassy spot among the trees behind a limestone escarpment, upon which a dawn scamper affords spectacular sunrise views.

Our camping setup is nowhere near as sophisticated as our caravan, but a cheap six-man tent, a vehicle awning, and slide-out fridge suffices in delivering the minimal comforts we need. The campground has respectable pit toilets and untreated bore water. Despite the hot daytime temperatures (up to 30 degrees in the dry season), it can dip below zero overnight. When we wake to a chorus of birds chortling and dingoes howling, it’s about eight degrees.

CATHEDRAL GORGE AND THE DOMES

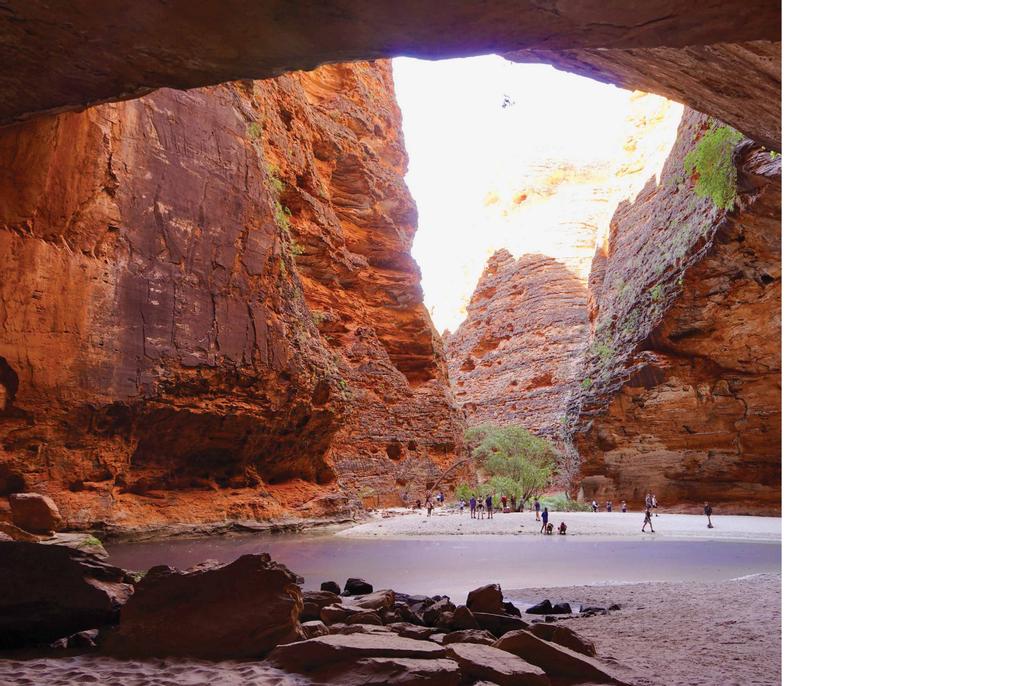

Cathedral Gorge from under the rock overhang

The beehive domes are the Uluru of Purnululu — a mystical landmark emblematic of a wilderness area unlike anywhere else in Australia. Glimpsing them for the first time brings joy to the soul. Once one hulking massif, the rock formations have been sculpted over 20 million years of wind, rain, and sandblasting from the Tanami Desert. Some are freestanding with perfectly formed domes while others are asymmetrical and flat-topped, as though their caps have been sliced off. Many are fused together, forming cliffs up to 250m high. All have distinctive orange and grey bands. The grey pigment is algae, formed in layers with higher clay content, while the drier orange bands are high in iron oxide (rust).

The 700m Domes Walk, at the southern end of the park, is one of Purnululu’s easiest and most rewarding circuits. As if drifting among these ancient towers is not captivating enough, there are curious termite mounds protruding in their midst, like ghoulish cloaked statues. Then there’s the wildflowers. For a semi-arid landscape, the park is flush with them. Acacia dripping with yellow pipe cleaner spindles, Grevillea laden with lolly bags of yellow and red, and Mulla Mulla poking purple bottle-brush spires from the earth. There are 600 plant species in Purnululu (including 13 species of spinifex), together with almost 300 different types of animals.

Less appealing are the toads. On the Cathedral Gorge extension walk from The Domes (2km return) there are dozens of dead and dying cane toads colonising the last puddles of water in rock wells remnant from wet seasons past. The trail switches from smooth rock, to stairs, to sand, before funnelling into a gargantuan amphitheatre. In the wet, this would be a swirling torrent of water, but in the dry, all that remains is a pewter pond ringed by snow-white sand. After The Domes, Cathedral Gorge is the most photographed attraction in Purnululu.

It’s not until I take a scenic flight with Kimberley Air, several days later, that I fully appreciate the diverse formations and scale of the Bungle Bungle Range. From the air, the domes unfurl like a topographical map, swirly snail-shelled clusters that rise haphazardly from the parched plains. And there’s not one range, but a multitude. Satellite rock cities stand defiantly, with an occasional solitary dome marooned far from the mothership. Incised fractures in the clifftops hint at the gorges within, green streaks betraying flourishes of Livistona.

There are 14 designated walks in the park, ranging from short Class 2 strolls to the overnight Class 5 Picaninny Gorge Trek. We tick off the main sights as far as time and ability will allow (our son is only five). At sunset we take the short, steep walk to Kungkalanayi Lookout and enjoy a cold beer as the expiring sun sets the hills and ridgelines ablaze. The experience is not without sacrifice. Before the day’s out, we blow a tyre and will have to make the return trip without a spare. Mum would be petrified.

INDIGENOUS GROUPS

The Traditional Owners of the Purnululu area are the Karjaganujaru people, who have lived in the region for over 20,000 years. Their language is the Djaru, which is a Pama-Nyungan language. We wish to acknowledge Elders past, present, and emerging.

FAST FACTS

NEED TO KNOW

Purnululu is open during the dry season (typically 1 April to 30 November) and is accessible to high-clearance 4WDs and single-axle offroad trailers only. There are no supplies available in the park or rubbish bins. The access road to the main sites within the park is almost 50km long from north to south, so make sure you have sufficient fuel (enough for 200km of park driving).

FEES

Entry costs $15 per vehicle, per day (payable at the Visitor Centre, open 8am to 4pm). Alternatively, you can buy an annual Western Australia All Parks Pass ($120). Either way you will need to register your arrival at the Visitor Centre.

CAMPING

Both Kurrajong and Walardi campgrounds must be booked in advance online (book early, adults $13, kids aged 6-15, $3). No generators or campfires. All caravans and trailers must be taken straight to the campground or unhitched at the Visitor Centre. parks.dpaw.wa.gov.au/park/purnululu

UNHITCH

Bungle Bungle Caravan Park has secure caravan storage available ($20 a night). It’s also a convenient place to stay before and after Purnululu adventures, with powered and unpowered sites (from $35), clean amenities, and a convivial bar and outdoor restaurant, the ‘Bungle Baravan’, set around a campfire. bunglebunglecaravanpark.com.au

SCENIC FLIGHTS

Various outfits operate scenic flights over Purnululu including Kimberley Air Tours, which has regular two-hour fixed-wing flights starting at dawn from Kununurra. Adults $395, kids $345. kimberleyairtours.com.au