Heart of the Mulga Lands

Mulga (Acacia aneura) is a woody plant with silver-grey foliage that varies widely in habit, height and shape. It can form dense forests up to 15m high but typically occurs as a heath-like shrub of about 2m, interspersed among eucalypts and native grasses. In its ideal habitat, mulga can grow vigorously and is very long-lived — up to 250 years.

The species is well-adapted to the region’s hot, dry environment, where summer temperatures are extreme and annual rainfall is meagre and unpredictable. Mulga was a vital resource for Indigenous Australians who used its hardwood to make digging sticks, woomeras, shields and bowls. The acacia’s seeds were ground to meal for seedcakes, eaten with a honey-like gum from a lerp scale on mulga branches. European pastoralists used its durable timber as a building material and for fence posts, and the mulga leaves were a valuable fodder for livestock in times of drought.

The Mulga Lands are a mosaic of flat sandplains, undulating dunefields, ranges of long, low hills, and occasional sandstone mesas flanked by deeply weathered scarps. Within the national park, rugged hills surround a wetland system of semipermanent and ephemeral lakes, claypans, saltpans and alluvial grey plains associated with the Paroo River and its tributaries.

The Paroo River begins in the Warrego Range, west of Charleville and flows generally south for 1200km in a series of waterholes, lakes and wetlands that connect after plentiful rains. Although considered a tributary of the Darling, the Paroo usually ends on a floodplain (the Paroo Overflow) east of White Cliffs, about 270km south of the Queensland border. Very rarely, and only during large floods, does the river join the Darling just upstream of Wilcannia.

Mulga Country — and indeed most of Queensland — overlies the Great Artesian Basin, the largest and deepest aquifer in the world. It contains an estimated 64,900 cubic kilometres of water within a layer of porous sandstone that was formed about 250 million years ago. Pressure within the aquifer forces water through faults in the rock to vent on the surface in springs and soaks at temperatures of 30-100 degrees. There are more than 70 artesian springs in the national park, providing important refuges for endemic plants and animals in this semi-arid environment.

THE CURRAWINYA WETLANDS

Established in 1991, Currawinya National Park was one of the first and largest reserves in Queensland to conserve valuable ecosystems of the Mulga Lands Bioregion. Since then, it has been expanded to 344,000 hectares, of which nearly half comprises the internationally important Currawinya Lakes Ramsar wetlands.

The Currawinya Lakes form one of the richest and most diverse wetland systems of inland Australia. Its complex landscape includes five freshwater and two saline lakes, ranging in size from 3813ha (Lake Wyara) to pans of less than one hectare, as well as riverine waterholes and artesian springs. Some are permanent but most are intermittent, filling only after heavy seasonal rains or when the Paroo floods.

The two major lakes, Wyara and Numalla, are the centrepiece of this complex system. Although separated by only a few kilometres of sand dunes, they have different catchments and are chemically distinct, as reflected in the wildlife and plant communities they support.

The walking trail to Lake Wyara

Wyara is a closed lake that fills about every seven years but regularly dries to a vast white saltpan. Its clear, saline water supports dense beds of flowering lilies, pondweed and widgeon grass that attract plant-eating waterbirds, such as coots, ducks and grebes. Large populations of invertebrates provide abundant food for wading birds like sandpipers, avocets and stilts. Islands within the lake are significant breeding sites for Australian pelicans, black swans, Caspian terns, silver gulls and cormorants.

In contrast, Lake Numalla (2904ha) is fed freshwater by Boorara and Carwarra Creeks and overflow from the Paroo when it floods. It only dries about once every 20 years. The lake’s turbid waters are populated by shrimp and native fish such as yellowbelly, bony bream and spangled perch, which attract fish-eating waterbirds including pelicans, egrets, cormorants and darters. Extensive reedbeds along the shoreline provide protected breeding sites for ducks, grebes and spoonbills.

BIODIVERSITY

Currawinya’s diverse habitats support a rich array of native plant and animal species. At least 747 plants, 256 birds, 56 mammals, 94 reptiles, 23 amphibians, eight fish and a tortoise have been recorded in the park. Of these, some 23 species are classified as threatened, vulnerable or endangered. For all of them, the wetlands provide a vital refuge in times of drought and a critical waypoint for shorebirds during their global migrations.

The diversity and sheer number of waterbirds at the Currawinya Lakes are comparable with those seen in the Alligator Rivers region of the Northern Territory. Survey counts in excess of 100,000 birds are common at Currawinya and have occasionally topped 250,000. No other wetland complex in arid or southern Australia consistently supports such large populations of waterbirds.

One of the endangered animals in the national park is the bilby, which once occurred over much of south-west Queensland before predation by feral animals and competition with livestock drastically reduced its numbers and distribution. In 2001, a rehabilitation program began in the park with a colony of captive-bred bilbies inside a 25sq km enclosure surrounded by a predator-proof fence. The colony thrived for ten years until floods in 2011-12 damaged the fence, allowing feral cats and foxes into the exclusion zone to once again decimate the marsupials. The fence has been repaired enabling conservationists to re-establish the colony in significant numbers.

INDIGENOUS CULTURE

Indigenous people of many nations lived in the Mulga Lands for more than 25,000 years before the arrival of Europeans. The Budjiti people are the traditional owners of the Currawinya Lakes area, including the national park. The Paroo River, lakes and floodplains were an integral part of their daily lives, as evidenced at many sites across the park in stone arrangements, native wells, scarred trees, artefact scatters, quarries, hearths, middens and burial grounds. Currawinya still has great cultural and spiritual significance for the Budjiti, who work closely with QPWS in protecting their heritage and managing the national park.

EUROPEAN HISTORY

Thomas Mitchell was the first European to pass through the Mulga Lands, in 1846, while searching for a route to the Gulf of Carpentaria. He was followed a year later by Edmund Kennedy, who explored the Warrego River plain and reported favourably on the area’s pastoral potential. A further report by William Landsborough after his 1862 expedition triggered an influx of settlers who found the open plains ideal for sheep grazing.

In the mid-1860s, Cobb & Co established a coach depot at the intersection of two major stock routes on the Warrego River. The settlement that grew up around it was named Cunnamulla (an Aboriginal term meaning ‘long stretch of water’). Aided by the establishment of artesian bores, the wool industry boomed, and Cunnamulla became a prominent regional centre with transport links throughout south-west Queensland and to the Darling River at Bourke. Today, most (94 per cent) of the Mulga Lands is grazed by both beef cattle and sheep for wool, with goat production developing as another livestock industry.

THE PARK’S PASTORAL HERITAGE

The region’s pastoral heritage is a tangible and fascinating attraction for visitors to Currawinya National Park. Established in 1991, the park initially incorporated two pastoral properties, Currawinya and Caiwarro, which began grazing sheep and cattle in the mid-1860s. In its heyday, Caiwarro covered more than one million acres (405,000ha). In 2015, the Queensland government acquired three adjoining stations — Boorara, Werewilka and Bingara — effectively doubling the size of the national park. At the peak of its operation around the turn of the 20th century, Boorara station was regularly shearing in excess of 100,000 sheep in a season.

The Currawinya homestead complex includes a meat house, living quarters and woolshed pens. The massive shearing shed is remarkably well preserved and is open for inspection by visitors. Though little remains of the old Caiwarro Homestead, the site still has much to interest heritage enthusiasts. The layout of the homestead complex reflects the social stratification of station life, and the ruins give an insight into construction techniques of the time. Old pastoral machinery stands around the site and a short walk leads to the remnants of a pumping station on the bank of the Paroo River that was used to irrigate a fodder-growing area.

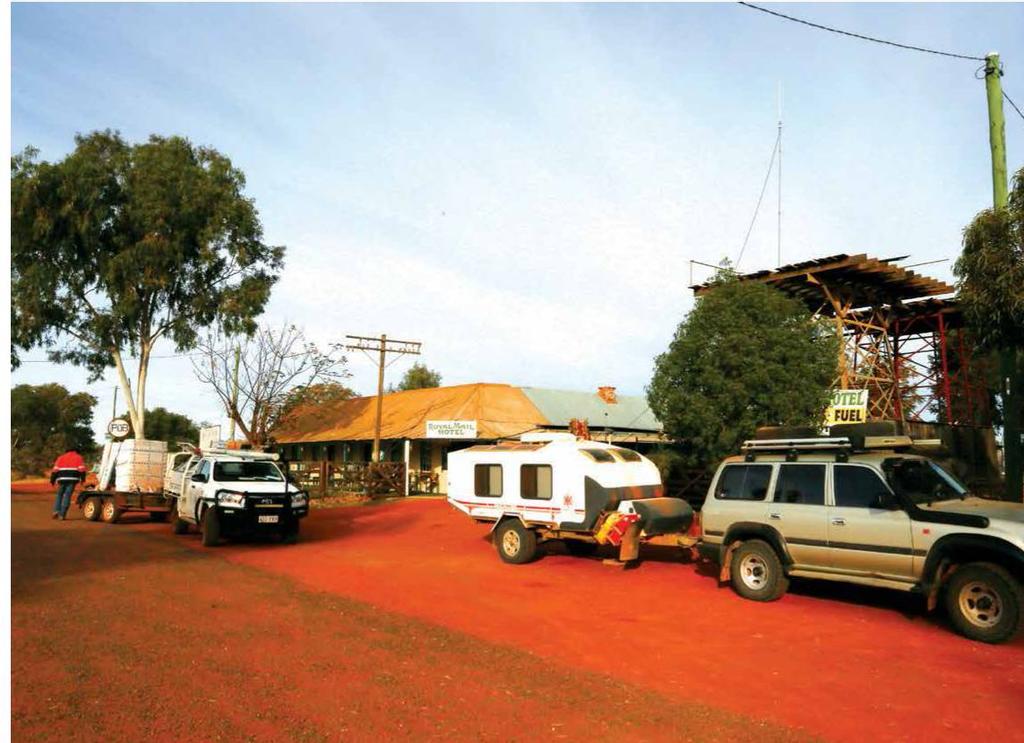

The Royal Mail Hotel at Hungerford, just south of the national park

TOURISM

Currawinya’s unique mulga landscape, wetlands teeming with birdlife and rich pastoral history make it a prime tourist attraction in the region. Straddling major roads between towns on both sides of the Queensland-NSW border, it’s easy to get to but remote and visitors need to be well-prepared and self-sufficient. Therein lies its appeal to adventure lovers who hanker for solitude and serenity in these wide-open spaces.

The park provides an authentic outback setting in which visitors can engage in nature-based recreation, such as no-frills bush camping, bird watching, photography and short walks associated with the many historical sites. Four-wheel driving enthusiasts will enjoy exploring the park on its extensive network of tracks, while Lake Numalla provides a scenic venue for swimming, canoeing and kayaking. Fishing is also permitted in some parts of the lake and in the Paroo River, and yabbies are plentiful in the waterholes during the winter months.

FAST FACTS

GETTING THERE

Currawinya NP lies 170km south-west of Cunnamulla, Qld, and 220km north-west of Bourke, NSW, via Hungerford.

All roads to and within the park are unsealed and impassable when wet. Although accessible by 2WD vehicles in dry conditions, a 4WD is recommended, especially for scenic drives within the park.

Check road conditions and weather forecasts before entering the park,

Best time to visit: May to October.

Fuel and supplies: available at Cunnamulla, Eulo, Hungerford, Wanaaring and Bourke.

CAMPING

- There are five camping areas: four along the Paroo River close to the main access road, and Myninya bush camp about 50km north-west of the ranger station.

- There are no facilities at any of the camping areas, except for Myninya (toilets, cold shower)

- Toilets and a cold shower are available at Currawinya Woolshed and there are toilets at Old Caiwarro Homestead site.

- No drinking water is available within the park.

- Camping permits are required and fees apply.

SEE AND DO

- Fishing, canoeing, swimming, birdwatching

- Scenic 4WDing

- The Granites

- Old Caiwarro Homestead site

- Currawinya Woolshed

MORE INFO

Queensland Parks

W: parks.des.qld.gov.au/parks/currawinya

W: parks.des.qld.gov.au/camping/bookings

Paroo Shire Council

49 Stockyard St, Cunnamulla

P: (07) 4655 8400

W: paroo.qld.gov.au/services/road-conditions