Journey to the Red Centre

Crossing the Australian continent through its vast Red Centre is a daunting challenge, one that many travellers prefer to avoid by sticking to the blacktop around the coast by the Nullarbor or the Top End. But there is one central east-west route which, though unsealed for much of its length, is scenic and readily accessible by most vehicles and vans — the Great Central Road (GCR). It also shortens the continental transit by hundreds of kilometres.

Beginning the adventure at Laverton, in Western Australia’s northern goldfields, the GCR stretches 1150km across the Great Victoria Desert to Yulara on the eastern boundary of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park in the Northern Territory. It forms part of the Outback Way that extends for another 1600km through Alice Springs to Winton in Queensland.

It takes about three or four days to comfortably travel the length of the GCR, but self-sufficient adventurers will find plenty to do along the way — wildlife watching, nature walks, indigenous art galleries and geo-caching — and quite a few overnight bush camps to extend the journey for a few more days. The route also connects a handful of roadhouses that supply fuel, power, showers and hot meals, which takes a lot of the angst out of remote long-distance logistics.

THE GREAT VICTORIA DESERT

At an estimated 424,400sq km, the Great Victoria is Australia’s largest desert, ranking third on a world scale behind the Sahara and the Arabian Desert. Its vast, sandy dune fields span more than 700km from the Eastern Goldfields of Western Australia to the Gawler Ranges in South Australia. On its arid margins lie more deserts — the Gibson in the north, the Little Sandy Desert to the north-west, the Nullarbor Plain in the South, and the Tirari and the Sturt Stony Desert to the east.

As befits its desert status, annual rainfall in the Great Victoria Desert (GVD) is a meagre 150-250mm, much of it from seasonal thunderstorms that are isolated and unpredictable. Summer daytime temperatures range from 32C to 40C, which fall in winter to 18C-23C with overnight minimums commonly below zero.

Much of the region is covered by a sea of rolling sand dunes, interspersed with low ranges, dissected tablelands and ancient salt lakes over Yilgarn bedrock — 2900 million-year-old granite that is some of the oldest rock on Earth. Only the hardiest plants survive in this inhospitable environment, typically open eucalypt woodlands, mulga scrub and spinifex grasses. But rain can transform this stark landscape overnight into a multi-hued spectacle of blooming wildflowers across the ochre-red sand.

Wildlife adapted to these harsh conditions includes few large birds or mammals — wedge-tailed eagles, emus, kangaroos, wallabies and feral camels. By far the most numerous and diverse of the desert-adapted fauna are reptiles, more than 100 species that includes skinks, geckos, snakes and two large monitor lizards, the perentie and the sand goanna, which can both exceed 1.6m in length. Australia’s largest land predator, the dingo, also prowls the region.

Despite some incursion by intrepid pastoralists and miners, the GVD has remained steadfastly unconquerable and largely unexplored. In 1875, Ernest Giles became the first European to cross the desert from east to west, naming it after the then-reigning British monarch, Queen Victoria. David Lindsey's expedition crossed the region from north to south in 1891.

Frank Hann came looking for pastoral land and gold between 1903 and 1908. During the 1950s and early 1960s, nuclear weapons trials were carried out by the United Kingdom in the eastern parts of the desert at Maralinga and Emu Field. Len Beadell explored the region for the Australian army, surveying and building roads in the 1960s, including the Gunbarrel, Connie Sue and Anne Beadell ‘Highways’, associated with the Woomera rocket and weapons testing range.

Harsh climate and isolation render the Great Victoria region one of the most sparsely populated and undeveloped areas of Australia. Only a small proportion (8 per cent) is grazed, mainly along its western margin, and there are no major population centres, except for a number of small communities within vast Aboriginal reserves.

SPINIFEX PEOPLE

The GVD is the traditional country of the Pila Nguru, often referred to as the Spinifex People, a name derived from the native grasses that dominate the arid landscape which supports their traditional hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

The centre of their homeland is Tjuntjunjara, some 700km east of Kalgoorlie, perhaps the most remote community in Australia. The Spinifex Arts Project was established in 1997 to support the Native Title claim by documenting the claimants' birthplaces and depicting traditional stories in large, boldly-coloured acrylic ‘dot paintings’.

The art of Spinifex People has been presented at solo and group exhibitions in major cities around Australia and overseas, and is keenly sought by collectors and institutions.

EXPLORING LAVERTON

The small town of Laverton sits at the western end of the GCR, 950km northeast of Perth via the Great Eastern Highway and Kalgoorlie. Before the arrival of Europeans the desert around Laverton had been inhabited by people from the Wangkatha Aboriginal language group for thousands of years.

Originally established as the British Flag Mine in the gold rush era of the 1890s, Laverton was renamed in 1900, in recognition of Dr Charles Laver, a bike-riding humanitarian and mining entrepreneur who worked tirelessly as the town’s doctor for many years. A bronze statue in the main park stands as a tribute to his civic contributions. By 1903, the town had grown to a population of 3500, with a reputation as one of the wildest settlements in the goldfields.

Nowadays local attractions include the Great Beyond Explorers’ Hall of Fame, the historic Police Station Complex and the Outback Art Gallery. The Laverton Caravan Park on the outskirts of town isn’t flashy but it’s conveniently located near the junction of the GCR and local shops, and makes a good base for preparation at the start of the journey or a peaceful rest stop after the desert trek.

GILES BREAKAWAY

Just 50km northeast of Laverton, a sign directs travellers to one of the journey’s most striking and colourful attractions, the Giles Breakaway. The short side-road ends at a scenic rest area (and informal bush camp) on the rim of a plateau overlooking a shallow canyon.

The plateau was once a bed of layered sediments beneath an ancient sea, exposed to the elements when the sea drained away. Erosion has carved away the hard caprock and etched the softer substrate into a multi-coloured escarpment of crumbling boulders. The sandy floor of the canyon opens southward to reveal the sprawling expanse of desert beyond.

On your way here, call into the small Aboriginal community of Cosmo Newbery, about 100km northeast of Laverton. Named after industrial chemist James Cosmo Newbery, the community features a health clinic, school, communication centre, fuel station and shop.

BEGULL GNAMMA HOLES

About 180km further on from Giles, where the road skirts the eastern shore of Lake Throssell, lies another of the desert’s geological wonders, a series of rockholes, known to the local Indigenous people as ‘gnamma’. A gnamma is a deep narrow hole in a granite outcrop that acts like a natural tank, holding water that is replenished from underground stores of decomposed rock and rainwater run-off.

They were one of the main sources of water for the nomadic Aboriginal people and, for European gold prospectors who ventured here in the 19th Century, a gnamma was often a more important and welcome find than the gold itself.

The Beegull Gnamma Holes form the largest group of tanks in the area. Atop the hill here is a large white-painted cross erected by Aboriginal christians in 1991 and a stone cairn dedicated to “RB” (Beegull), whose connection with the site is now lost in the sands of time. The waterholes attract dingoes, kangaroos, vast flocks of zebra finches and iridescent green budgerigars during the dry season when surface water is scarce on the arid plains.

TJUKAYIRLA ROADHOUSE

Located 310km east of Laverton, the roadhouse provides a welcome pitstop for travellers along the Outback Way. And as part of the road to the east is also a landing strip for the Royal Flying Doctor Service, it is also a place for rescue in times of medical emergency.

Travellers can obtain fuel (diesel and Opal), minor mechanical and tyre repairs, meals and basic supplies, as well as accommodation ranging from motel-style units to camping (powered and unpowered) with an amenities block and camp kitchen.

WARBURTON

The community of Warburton (Mirlirrtjarra) was established as a missionary settlement on the banks of Elder Creek, 570km from Laverton, in 1934. It was named after explorer Peter Warburton, the first European to cross the Great Sandy Desert.

Today, the community boasts a predominantly indigenous population of around 500 residents and facilities that include an airstrip, a community store, health clinic, school, open-air swimming pool and sports field.

Warburton Roadhouse, located outside the community on the GCR, provides fuel (diesel and Opal), minor mechanical and tyre repairs and accessories, meals and grocery items. Accommodation is also available in self-contained units, motel-style rooms and caravan/camping sites (powered and unpowered).

YARLA-KUTJARRA

For self-sufficient travellers who prefer the solitude of bush camping, the Yarla-Kutjarra campground 100km east of Warburton offers a good alternative. This spacious camping area was constructed by the local community with plenty of sites among a small group of breakaways that provide protection from the wind. The basic facilities include a drop toilet, shelter and an interesting Interpretive sign explaining the bush tucker in the area.

WARAKURNA

The large Aboriginal community of Warakurna is located at the eastern end of the majestic Rawlinson Range, 260km northeast of Warburton. The local Yarnangu people are the traditional owners of lands that encompass 186,000sq km of the Gibson and Great Victoria deserts. It’s home to the Yurliya Gallery which promotes paintings, handwoven baskets, sculpture and wooden artefacts produced by the Warakurna Artists.

The Warakurna Roadhouse stands on the outskirts of the community and offers fuel (diesel and Opal), tyre repairs, takeaway food, drinks, basic grocery items and local artefacts. Travellers are accommodated in self-contained motel-style units, backpacker rooms or on caravan/camping sites (powered and unpowered) with an amenities block and camp kitchen.

GILES METEOROLOGICAL STATION

Close to the Warburton Community stands the Giles Meteorological Station, named in honour of Ernest Giles, who explored the area in 1874. Situated in the foothills of the Rawlinson Range, 350km west of Yulara, the Giles Meteorological Station is one of the most remote weather stations in the world.

The station was established in 1956 by the Weapons Research Establishment (a division of the Department of Defence) to provide weather data for the UK atomic weapons tests at Emu Plains and Maralinga and to support the rocket testing program based at Woomera. It was transferred to the Bureau of Meteorology in 1972. The facility is linked via landline and satellite to Melbourne where it is included in the national and international networks.

Giles is also the resting place of the Caterpillar grader which was used to build the Gunbarrel Highway and other roads in the area under the supervision of surveyor Len Beadell. It is estimated that, during its 10 years of operation before retirement in 1963, the grader travelled more than 30,000 kilometres. Also on display is wreckage from the first Blue Streak missile, launched from Woomera on 5 June 1964.

KALTUKATJARA (DOCKER RIVER)

From Warakurna, the GCR tracks east for nearly 100km to Kaltukatjara (Docker River), just inside the Northern Territory border. Despite the corrugations, the views of the magnificent Rawlinson and Anne Ranges make this a popular stretch of the journey. These folded, rusty-red hills are dotted with conspicuous dome-shaped peaks, such as Rebecca Hill, Mt Gibraltar and Gill Pinnacle, which were important landmarks in guiding Aboriginal nomads and European explorers to perennial waterholes within their shaded gorges.

After crossing the WA/NT border, the GCR becomes the Tjukaruru Road and soon arrives at the Kaltukatjara Aboriginal Community, about 225km west of Yulara. The site was given its European name (Docker River) by Ernest Giles in 1872, after the watercourse on which it stands, but the community has retained the original Aboriginal place name (Kaltukatjara) for the township.

The Docker River campground, signposted 1km west of the community, is a pleasant space set in a grove of shady desert oaks with views of sand dunes and the distant Petermann Ranges. At last report (August 2018) the toilet and shower amenities were in the process of being upgraded.

LASSETER’S CAVE

After leaving Kaltukatjara, the Tjukaruru Road skirts the northern edge of the beautiful Mannanana and Curdie Ranges, which are separated by the Hull River at a place called Tjunti. It was here that prospector Harold Lasseter took refuge in a small cave on his ill-fated expedition to rediscover a rich gold deposit (Lasseter’s Reef) he claimed to have found in 1897.

After about 25 days during January 1931, starving and dehydrated, Lasseter set out to walk the 140km to Mount Olga (Kata Tju?a), hoping to meet up with his relief party. In three days he covered 55km to Irving Creek in the Pottoyu Hills, where he died on about 30 January. His body was later found and buried there, and has since been re-interred in the Alice Springs cemetery.

The legend of Lasseter’s Reef continues to excite debate and ignite the imaginations of outback wanderers. Whether it is real or a grandiose hoax, his name is immortalised in the Lasseter Highway, named in his honour in 1983, which connects the Stuart Highway at Erldunda to Yulara township near Uluru.

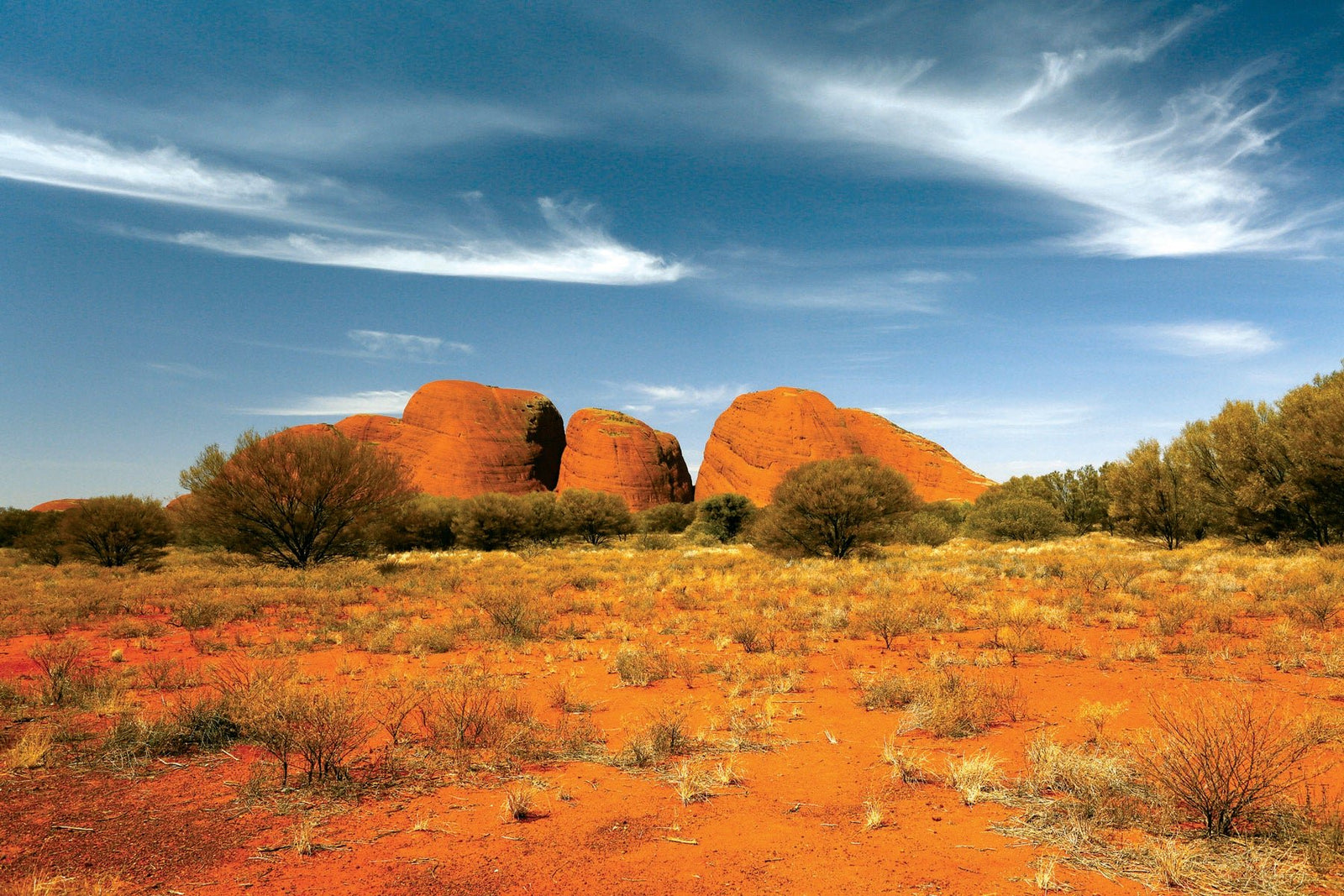

ULURU-KATA TJUTA NATIONAL PARK

After Lasseter’s Cave, the GCR enters its final stage towards Yulara. Sadly, in terms of road condition, it’s a case of saving the worst until last. As the Petermann Ranges fade from view, the distinctive profile of Kata Tjuta rises out of the desert ahead. But there is little chance of taking your eyes off the road, which is an uncomfortable sequence of dusty red sand, gnarly limestone gravel, ruts and deep corrugations for about 140km to the edge of the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. Here, mercifully, the bitumen kicks in and continues highway-like all the way to Yulara and beyond to Alice Springs.

After several days of seeing only a handful of cars and few tourists each day on the GCR, the abrupt return to ‘civilisation’ can come as something of a shock. But having come all this way (1115km) from Laverton across the world’s third largest desert, the allure of this World Heritage national park is simply irresistible.

Steeped in Aboriginal mystique and awe-inspiring beauty, these extraordinary natural wonders have been formed over hundreds of millions of years to become our national icons. You can’t come here and blithely pass them by. And after all those days of car travel, these spectacular landscapes offer the perfect opportunity to get out and stretch your legs – on The Valley of the Winds Trail and Walga Gorge Walk at Kata Tjuta, and the Base Walk at Uluru.

First-time visitors to the national park will probably want to stay overnight at Yulara and spend a few days exploring. Facilities include a post office, supermarket, medical centre, bank, fuel (leaded, unleaded, diesel and LPG) and mechanical repairs. Accommodation ranges from camping to five-star luxury. For return travellers, Alice Springs lies a smooth, five-hour highway drive away.

FAST FACTS

The Great Central Road (GCR) from Laverton (WA) to Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park (NT) is unsealed and may become impassable in wet weather. Check with local authorities on road conditions and closures.

The WA section is generally well maintained gravel but the NT section is sandy, rough and corrugated in places. It’s advisable to travel in a 4WD vehicle, although 2WD vehicles and caravans will survive the trip. Always drive carefully to the conditions.

The GCR traverses remote desert areas and the journey requires careful preparation. Make sure your vehicle is in good mechanical condition and carry a tool kit, essential spare parts, spare tyres, tyre repair kit and recovery gear. Get a detailed map and/or sat-nav device and carry a satellite phone or HF radio. Mobile phones have limited coverage.

Plan to be self-sufficient. Carry plenty of water, food and fuel, plus extra food and water in case of emergency. In the event of a breakdown, stay with your vehicle.

Do an accredited first aid course and carry a comprehensive first aid kit which is easy to access.

If travelling from east to west, dispose of all quarantine risk material (including all fresh fruit, vegetables, honey, seed, potatoes, onions and other such plants, etc) in the amnesty bin 20 km outside Laverton. A mobile inspector operates in the area and may issue fines for non-compliance.

The best time to travel on the GCR is during the cooler months from April to October. Warm, dry, sunny days are common during these months, although nights can be cold.

The GCR passes through Aboriginal land and it is a legal requirement for travellers to hold valid transit permits at the time of travel, one for each side of the WA/NT border. The permits are free and can be obtained online.

Along the GCR, camping (with fees) is available Laverton, Tjukayirla, Warburton, Warakurna and Kaltukatjara. There are also plenty of places for free bush camping (with no facilities) close to the road, including Giles Breakaway, Limestone Well, Minnie Creek Road rest area, Camp Paradise, Manunda Rockhole Yarla-Kutjarra, and Lake Throssell (dry weather only). Be respectful of the country and take all your rubbish with you.